Piauí

Lawless land

CLAUDIA REGINA SANTOS

Claudia Regina Santos has been threatened to death at least five times. She lives in the south of the state of Piauí, in a region outsiders call the “last agricultural frontier”. Claudia has worked in defense of the rights of rural communities for over twenty years, and because of that, her life has been marked by the agrarian conflicts of her region.

Claudia was born and raised between Bom Jesus and Currais; two small municipalities located about 700 km from Teresina, the state’s capital. Known for its fertile land and abundance of water, the area is highly coveted by soy farmers and international investment firms who buy farmland in Brazil.

The region is one of the most important to the expansion of soy in the country and Bom Jesus is presently among the top ten most productive municipalities in the Matopiba. According to a study done by the Universidade Federal de Goiás (federal university of Goiás), between 2007 and 2015, almost fifty thousand hectares were cleared in Bom Jesus – an area equivalent to fifty thousand official soccer fields. Approximately 80 percent of this area was converted into farmland for soy or other annual crops.

The municipality’s territory, comprised of many old sertanejo communities, is the reason behind land disputes that frequently escalate and result in conflicts. That was where one of the most violent conflicts in the state took place in 2008; a story that still makes Claudia cry when she tells it.

” This is the land of lawlessness. As it is said around here: When orders are given, those with sense obey.”

Claudia Regina Santos

It was early May when Claudia, at the time part of the leadership of the rural workers’ union (Sindicato do Trabalhadores Rurais), received the news that families from a small community had been violently dispossessed of their land by a man who claimed to own the area. The Sucruiú community, an isolated neighborhood located 140 km from the central area of the small municipality, had been dealing with attempted invasion of their lands for years. The community had already won a court case against Abrão Ildeu da Silva, the man who claimed to own the land. “But then, even after the judge said we had won, he went to court again and came back here.” says Antônio James, a resident.

On May 8th, Abrão arrived at the community with a court official, four policemen, and a bulldozer. Claudia says the residents were forced outside their homes and made to watch as the bulldozer razed their houses. “They only spared the workers’ lives because those came out of their houses. At that moment, they had to choose between losing their houses or their lives.”

Claudia says the grileiro’s A person who takes possession of land by means of false deeds. employees not only razed the houses, but also destroyed crops and poisoned the water supply. “The families lost everything, they really were dispossessed.”

After the attack, representatives of the union and of the Pastoral da Terra (Pastoral da terra commission) headed to the community to assess the damages and rescue the distressed families. Around 7:30 pm, they came across a roadblock on their way back to town. ” I saw lights and suggested we turn back. I found that odd because I knew there was no electricity in that area. Machismo won the discussion and we did not turn back, and suffered the consequences…” remembers Claudia, her voice choking with emotion. “There were so many jagunços (hired guns).”

The first pickup truck was attacked, its tires were punctured and they started hitting people. The back of the truck was filled with residents, many of whom were children, teenagers, and older people. They broke a nine-month-old baby’s collarbone. An amateur filmmaker had accompanied the rescue mission; his equipment was destroyed and he was beaten and imprisoned. Some people were beaten with wooden clubs. “It was barbaric. People were trying to flee into the woods and they kept on shooting. Everyone was running and the bullets kept on coming, and coming,” recounts Claudia.

Luckily no one was killed that night. “But death did come as a result of that conflict; a pregnant woman, whose house had been destroyed, fainted, barely came to, and was sick for the rest of her pregnancy. She later died giving birth.” Claudia laments. She believes people’s homes are sacred. ” A woman died, spilling her blood for a piece of land that had always been denied her.”

Claudia says they pressed charges at the time and even took the matter up with the district court. “All we could do was bring the matter to them, really, because in all these years no action was taken.” Years later, Claudia found out that no legal proceedings concerning the attack had ever been filed in the Bom Jesus district courts.

After the incident, in 2012, the Incra institute (Institute of colonization and agrarian reform) established an official rural settlement for the families in the disputed area. The Sucruiú community became the Rio Preto settlement. However, even twelve years after the attack, those forty-one families still live in fear of losing everything again. In June 2019, two men with bulldozers invaded the settlement and threatened to destroy everything. The residents are still under threat despite the settlement being officially protected. “Since nothing was settled in court, they are still around today, tormenting people.” says Claudia. According to her, the grileiro who claims ownership of the land and was responsible for the attacks intends to use the land to plant grain and raise livestock.

“It happens all over the state of Piauí; agribusiness applies pressure and the administration provides no protection.”

Claudia Regina Santos

The case of the Rio Preto settlement is one of many similar conflicts that take place all over the Piauí territory.

The disputes of Bom Jesus have much in common with other land disputes occurring on agricultural frontiers in the Cerrado. On one side, are the posseiros (occupants), who have always lived in the region, cultivating crops in small plots and raising cattle freely on the plateaus – on land that most often than not, has never had fences nor deeds of ownership; on the other side, are the farmers who want to ready the land for monoculture and livestock.

When both sides meet, conflicts emerge. Farmers claim ownership of the land on which the communities live, traditional residents refuse to leave, judicial decisions are dragged, emotions flare up, and violence ensues. According to Latentes’ database on agrarian conflicts, there were 112 areas with ongoing social-environmental conflicts in Piauí in 2019. One hundred and eight of those conflicts were in places where settlements had been officially established. In the area around Bom Jesus, the Pastoral da Terra commission logged twenty-seven places with ongoing disputes.

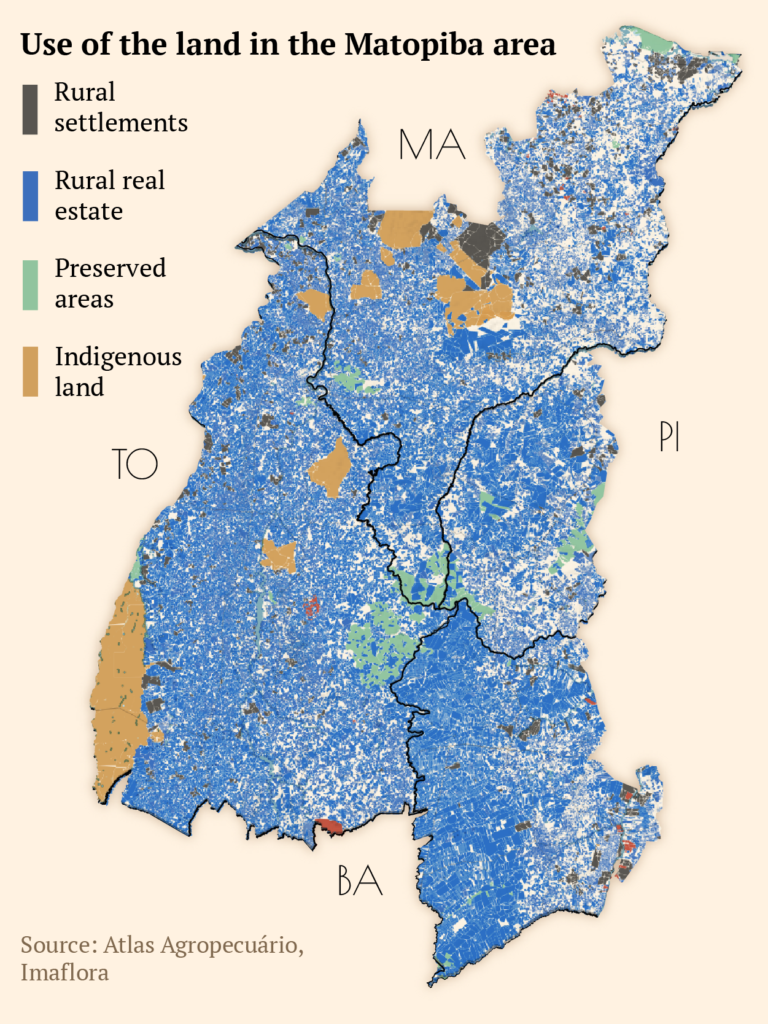

A study by Greenpeace in the Matopiba states that, “it is hard to know for sure which of the present deeds of lands are entirely legal and which would actually hold up upon further scrutiny in court.” Illegal possession of land by grileiros, absence of documentation, and the interest of agribusiness in the region have affected its residents for decades.

The Pot of Gold

The Matopiba is where most of the still-existent Cerrado of the northeast is located. Today, it is one of the most coveted regions by agribusiness and has been a huge draw for companies specialized in mechanized agriculture for export. Between the years 2000 and 2014, the area of soy farmlands increased from 1 million to 3,4 million hectares, a growth of 253 percent for that period. The production is very concentrated, not only in geographical terms, but also in terms of the groups that make up the agrarian social structure of the Matopiba.

The flat lands, the chapadões (plateaus) far-removed from large urban centers, the rich groundwater reservoir, and the supposed “unoccupied” land have made the area attractive. The most recent occupation of the area occurs because of the belief that the Cerrado is a Biome that can be overtaken in order to “make way for productivity”.

In the 1970s and 1980s highways were built in the region and the second phase of the Prodecer (the Nippon-Brazilian Program for the Development of the Cerrados) initiative began with the intent to incentivize the production of soy for export. The second phase launched the expansion of the agricultural frontier into the northeast, where lands were much cheaper. Thus, through government incentives, farmers from other states made their way to Matopiba.

In the state of Piauí and around Claudia’s municipality, outsiders began to arrive in larger numbers starting in the 1990s. The process of transformation of the native landscapes into farmland, primarily for soy cultivation, has continued and intensified between 2000 and 2015. It was at the end of this period that, then-president Dilma Rousseff signed a decree delimiting the area and implementing sanctions on the expansion of soy in the region.

The interest of foreign companies and the buying and selling of land as financial assets by investment firms is gaining attention today. Researcher Arilson Favareto believes that what sets the Matopiba area apart from other regions, such as the Amazon, is that the conflicts and the appropriation of land in the region increasingly involve transnational companies. In a book, he explains that this is part of a global trend of land grabbing, which has intensified since 2008 with the growing interest of investment firms and the agriculture industry in the land of developing countries.

The struggle to survive

According to researchers, the consequences are dire for the traditional populations being deprived of access to areas that guarantee their sustenance – pasture land for their livestock, areas of fruit gathering, and farmland. In addition, the communities also suffer from the overall dryer conditions of the ecosystem and a decrease in rain.

Cláudia says the planting cycles in her region have been irregular. She has noticed changes in the climate for the past five years at least. ” We had years with no real rain, and when it did rain, it was unsteady and too strong. It poured so much a dam burst.”

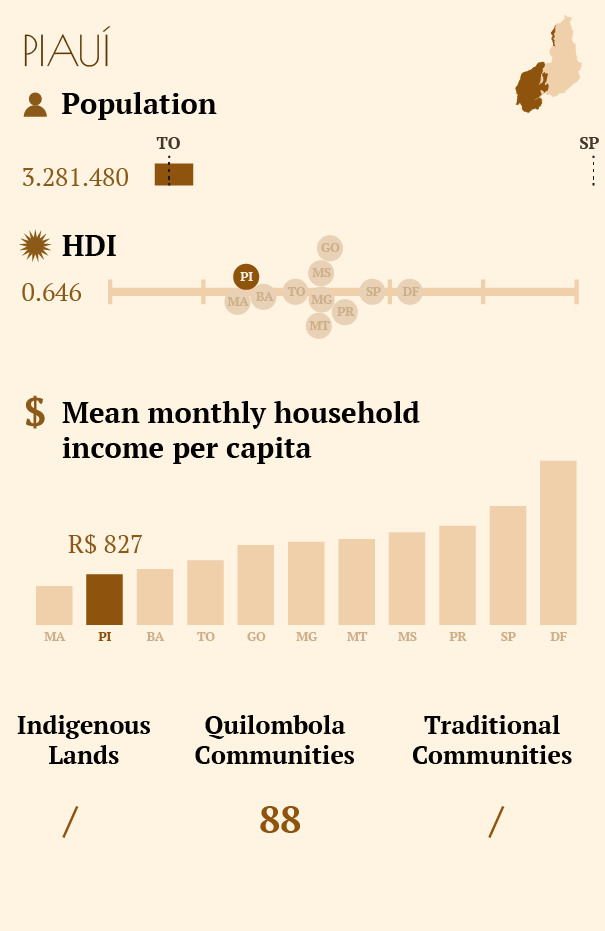

Together with the environmental impacts of the agricultural model taking over the Matopiba, comes a lack of improvement in social indicators in the areas where the model is implemented. In practice, the high yields do not translate to a higher quality of life for the local populace. Municipalities that set records in agricultural productivity report indicators of social development below the national average.

According to a study on soy production in the Matopiba, an increase in the GDP per capita occurred in areas where there was an increase in production of the grain, yet health indicators such as child mortality rates and the number of doctors per ten thousand inhabitants, worsened. The income generated by the yield is not distributed among the local population, in part because of the concentration of landholding, and because poorer people are excluded from the job market, with no access to new opportunities that could generate growth on a local level.

Claudia still leads a political life in defense of traditional rural communities and dreams that people will one day have decent living conditions. ” I dream of a land where justice exists.”

” It is better to die here, even in the middle of a conflict, than to go hungry in a suburb of a some large city elsewhere.”

Claudia Regina Santos