Mato Grosso

The steamroller

TSITSINA XAVANTE

Tsitsina Xavante lives by the rivers but far from the sea. Her neighbors are two crystalline streams and an affluent of broad rapids. The latter, the Owäwe, is the ancestral river of souls. Her home, the Namunkurá tribe, is surrounded by tall dark trees, characteristic of the riparian vegetation found along the banks of rivers in the original landscapes of the Cerrado.

The São Marcos indigenous territory where Tsitsina and a part of the Xavante people live is a stronghold of preserved vegetation in the eastern part of the Mato Grosso state. The rich aquifer found on the indigenous territory can be explained by the formation of the state itself; it is literally the ‘birthplace of waters’, where the springs of the Amazon and Tocantins-Araguaia basins are located, two of the three largest drainage basins in South America.

The abundance of water that is essential to Tsitsina’s life also fosters biodiversity. To this day, the 188 thousand hectares of the indigenous territory (roughly the size of the São Paulo municipality) has preserved sections of the “various types of landscape” of Brazil’s oldest Biome.

The Xavante A’uwe Uptabi people, who have lived in the region for over two hundred years, identify seven different landscape formations of the Cerrado on their lands. They have a name for each type and recognize their unique features, thus structuring their life around what they can harvest and gather in each of the parts of the Cerrado.

For Tsitsina and the Xavante people -who call themselves A’uwe Uptabi- life does not take place in the Cerrado, but rather it originates from it. These are a people integrated with the Biome, with a particular way of seeing, thinking, and acting within the Cerrado. The Xavante culture simultaneously nourishes and is nourished by the Biome in an efficient and abundant cycle that has been documented by various researchers in the past sixty years.

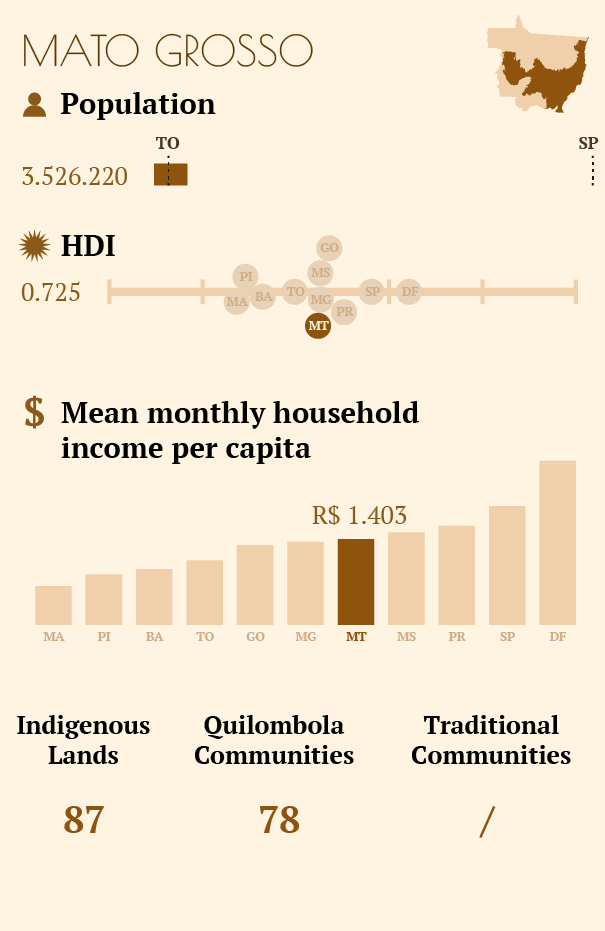

Counting over 22 thousand people, today, the A’uwe Uptabi are the largest ethnicity of Mato Grosso. Nine indigenous territories exist with more than 300 tribes spread out between the eastern and northeastern parts of the state. The areas officially preserved and demarcated as indigenous land are oases where remnant parts of the Biome still exist. According to official numbers from the Ministry of the Environment, close to 40 percent of the Cerrado has been destroyed in the state.

” There is a noticeable change in the climate and a reduction of our biodiversity. There is progressively less rain, and less fruit.”

Tsitsina Xavante

Tsitsina says the transformation of the original environment in the areas surrounding the territories also affect the balance of life on the territories themselves, where the Cerrado still exists.

The bulldozer

Mato Grosso is an established leader in Brazilian agribusiness. It is the biggest producer of soy and possesses the largest herd of cattle for meat in the country. It is also among the states with the highest rate of deforestation.

In the last two decades, the sate of Mato Grosso was responsible for 16 percent of all verified deforestation of the Cerrado, amounting to the highest rate among all states, and 31 percent of deforestation of the Amazon, the second highest rate in the country. In 2019, it was the state with the second largest area of deforestation, behind Pará.

A recent study correlates the devastation of the environment to the cultivation of soy. The study reveals that deforestation is presently more of a threat to the Cerrado than to the Amazon. Devastation has slowed in the Amazon Biome since the moratorium on soy. Unfortunately, the Cerrado does not have the same protection; between 2012 and 2017 roughly 880 thousand hectares of Cerrado were cleared in the Mato Grosso, an area seven times greater than the Rio de Janeiro municipality.

“Traditional communities are being surrounded. They are being cornered by agribusiness,” points out federal prosecutor, Wilson Rocha. Wilson is part of a group created within the Federal Prosecution Service to increase protection of the Cerrado.

He believes the Biome suffers because the agricultural expansion does not take social and environmental aspects into consideration as a part of its project.

” Agribusiness’ model is like a bulldozer, crushing anyone in its path.”

Wilson Rocha

Traditional communities are the ones most affected by what the prosecutor sees as “an unbalance of power more prominent in the Cerrado than in the Amazon.” Wilson says the communities of the Cerrado have only recently begun to organize and claim their rights, and as such, are still less structured than the communities of the north of the country. ” If you look at the indigenous communities of Mato Grosso on a map, you will see them as green dots surrounded by enormous areas of deforestation.”

Airborne contamination

Hiparidi Toquira lives on another Xavante territory, not too far from Tsitsina’s tribe. The inhabitants of the Sangradouro indigenous territory share a reality with the seventy-eight other indigenous territories in the state; their land is protected and officially demarcated, but their quality of life and the environmental balance necessary for the Xavante way of life is not guaranteed because of it.

Hiparidi explains they have had problems with pesticides because of the surrounding land occupied with soy and/or cattle farmlands. The pesticides contaminate their water supply and the animals that make up a part of their food source. Hiparidi says, “Naturally, the animals seek refuge on our lands. When the corn is sowed, they leave, feed, and then come back. This is very complicated for our children’s health. We have had diarrhea and other diseases we previously did not have. ”

In addition to being one of the states with the largest agricultural production, Mato Grosso is also a leader in the use of fertilizers and pesticides. A 2015 study done by the Ministério Público do Trabalho (Ministry of Labor) revealed that exposure to pesticides is seven times greater in Mato grosso than in other areas of the country.

Crop dusting is common on most large farmlands in the area, which is a problem for local indigenous and rural populations in general. The Urubu Branco indigenous territory, located in the northeast of the state, for example, is separated from a soy farm by an area only 500 meters wide. As expected, they feel the effects of crop dusting. The region is an ecotone between the Cerrado and the Amazon rainforest and is home to the Apyãwa people, known as the Tapirapé.

In that same region, there have been reports of rural communities being expelled from their land because of pesticides. The pesticide used on farmlands is carried by the wind and spreads through the air, eventually reaching the surrounding communities and causing disease in people, crops, and animals. Agronomist and professor at the Instituto Federal de Mato Grosso (Mato Grosso federal institute), Polyana Rafaela Ramos claims there are many cases of smaller settlements located on lands valued by agribusiness having suffered such attacks. In a piece by the Agência Pública investigating cases of the effect of crop dusting on local communities she stated that, ” The pesticide threats are concealed and/or direct. As they buy surrounding lands, livestock and crops start to die, and people get sick. Who is going to put up with it that?”

Despite accounts from rural workers and natives about diseases caused by surrounding soy farmland, courts rarely ruled such cases. Research on the presence of pesticides in river water is expensive, and as much as the Urubu Branco residents relate the outbreak of diseases, no scientific investigation has been undertaken to check the concentration of pesticide in the territory’s waters and its fish. The same is true of the waters that flow across farmlands before they reach the territory of the Xavante.

Because many of the effects of pesticides take years to manifest on the human body, rural communities exposed to the products await the unknown. Some studies in the region examine the correlation between pesticide exposure and the onset of diseases. One such study by the Universidade Federal do Mato Grosso (Mato Grosso federal university) found a significant connection between the use of pesticides and a decline in health. A different study from the same university looked at cases of congenital malformations in babies from the municipalities most exposed to pesticides in the state.

The rural and traditional communities that inhabit the Cerrado in Mato Grosso have become more and more distressed with the advance of agribusiness over the years. For Tsitsina, this reality is a nightmare she wishes to awaken from. She explains: ” a recent study says our Biome will be destroyed if deforestation and projects that affect the water sources continue as they have so far. I dream and hope that nothing of what this study says will come true.”