Bahia

The land grab and the fight for the territory

LUSINEIDE DOS SANTOS

As night falls, Lusineide dos Santos lights the candles. Her community is situated deep in a valley between two plateaus in the western part of the state of Bahia and does not have electricity. The families depend on solar panels, but the equipment often malfunctions so they live without refrigerators, the Internet, and sometimes even lamps. Isolated, the residents of the Cacimbinha community live 130 km away from Formosa do Rio Preto, a municipality ranking among those with the highest revenue derived from agriculture in the country.

From the dirt road riddled with holes that joins Lusineide’s community to the town center, one can see parts of the enormous soy farmlands nearby and their automated harvesting machines. It has been over forty years since companies dealing in commodities arrived in the region and began planting grain on the plateaus. Today, the municipality’s area is crisscrossed with farmland that is harvested using advanced technology, as has become the standard of mechanized farming in Brazilian monoculture.

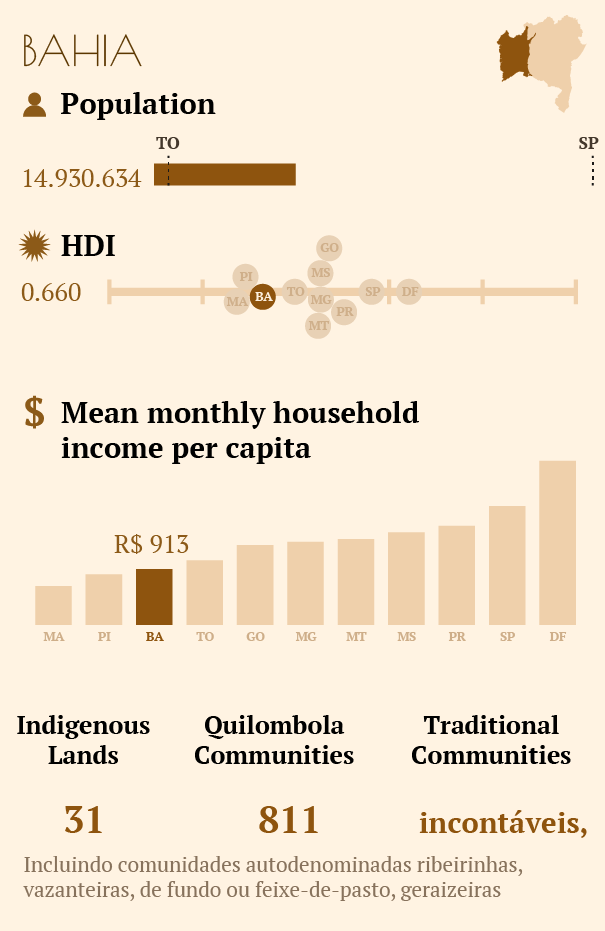

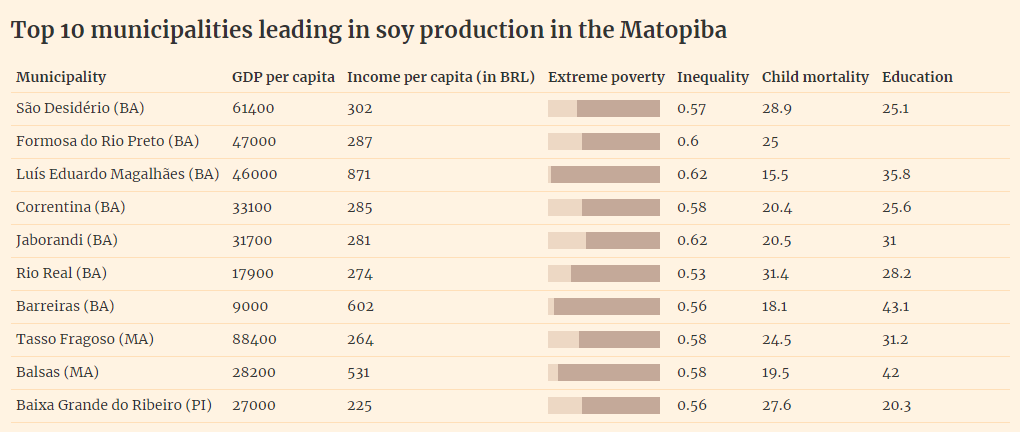

Despite the proximity of the farmland to the Cacimbinha community, the infrastructure of the farms has not been extended to the families who live in the valley. Actually, the paradoxical image of a community with no electricity and its neighboring farmland equipped with highly modern technology is only one of the many contrasts in the region. There is much money, and much poverty in the municipality of Formosa do Rio Preto. The average income per capita of the area is close to 67 thousand Brazilian reais, however, half of the population (53,6 percent) receives less than half the minimum wage per month.

The human development indicators are not on the same level as the record productivity of the area. Despite the gross income being among the 200 highest in the country, Formosa is also one of the 2.000 cities with the highest child mortality rate according to the IBGE. In 2018, when the district rose to fifth in the ranking of most revenue derived from agriculture, almost a third of the population of Formosa was living in extreme poverty.

This picture of inequality is not characteristic of Lusineide’s municipality alone. Other towns of the Bahia Cerrado, whose economies are based on the production of commodities, have similar indicators. The same is also true in municipalities throughout the Cerrado, in other states where agribusiness has been investing over the past decades.

A 2018 Greenpeace study analyzed the social and economic indicators of Matopiba. Researchers found that districts that have both high agricultural productivity and above-average indicators of well-being in the population are a minority. The study reports that the common belief that agribusiness enterprises bring development to the Matopiba has no basis in reality. On the contrary, the expansion of soy and livestock farmlands over the areas of the native Cerrado yields profit for few companies and landowners, leaving a trail of environmental and social damage to the local population.

The advance of farmlands

The arrival of soy farming in the vicinity of the Cacimbinha community has been a traumatic experience. The first outsiders bought deeds to the lands around the community in the late 1970s, but over time, this process has become quite irregular. Lands have been taken by means of fake documents in what has become one of the largest areas of illegally possessed land in the country, according to Incra (Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária – National institute of colonization and agrarian reform).

This vast area has had several owners during this process, and has been sliced up and resold. As such, local communities gradually became restricted to the valley. Today, the plateaus previously used by the traditional populations for livestock grazing and fruit gathering have been completely overtaken by soy farmlands. In a process all too similar to what happens in other areas of the Cerrado, as years went by, residents of Cacimbinha found themselves completely surrounded by monoculture plantations.

“The biggest problem though, has been having to fend off invasions in recent years,” Lusineide points out. The complex of neighboring farms, called Condomínio Cachoeira do Estrondo, has surrounded the traditional community’s territory and seeks to expel its residents in order to declare the area a “conservation area”.

With the changes to Brazil’s forest code implemented in 2012, the Estrondo farms no longer had sufficient conservation areas as required by the new law and decided to try to annex the territory of the local communities. They put up fences and installed security gatehouses to prevent access and intimidate the residents. Whenever a resident wished to leave one of the communities, he/she had to present their IDs to the heavily armed guards. Lusineide says that as the communities began to resist, the intimidating efforts increased. The attacks worsened when the communities organized and sought legal action to maintain possession of their territories. The farms’ private security guards and military police officers removed the communities’ cell tower. Rural workers were taken into custody and prohibited to move freely with their livestock through land that had been illegally fenced off.

” When the conflict got nasty, they began to bar people, burn cars, kill livestock, and they even shot someone.”

Lusineide dos Santos

The dispute dragged on for years. The threats and violations of human rights against the traditional communities only ceased when they were granted possession of the land in the valley in court. “We fought, and fought till the end. Even after someone was shot we did not give up, because, where would we go if we lost?” remembers a resident of Cacimbinha. The farm complex challenged the decision on all levels of the courts but possession remained to the communities.

The complex was forced to remove the fences and gatehouses. Today the communities are seeking indemnities for the harm done. According to Liliane Campos, a lawyer directly involved in land disputes in the Bahia Cerrado, this case is noteworthy because court rulings that favor traditional communities tend to be the exception.

A constant battle

Traditional communities in the state of Bahia – fundo de pasto, ribeirinhas, geraizeiras, quilombolas, and others- live in constant tension. In many areas, old and frightening land disputes resurge, and in others, new disputes and threats have surged in recent years as a consequence of the expansion of the agricultural frontier.

A study by the Pastoral da Terra commission done in 2019 identified 130 land disputes involving communities in the state of Bahia. The study considers conflicts such as that of the Cacimbinha community, but also lists several disputes involving small farming communities, quilombolas, indigenous, sem terra, and other communities. According to the study, considered a reference on the topic, the state of Bahia was the state with the third largest number of disputes, behind Maranhão and Pará.

” Illegal possession of lands affects traditional communities all over the state. Those of us involved in the reality of Bahia know this is a widespread matter.”

Liliane Campos

Liliane Campos says that legislation is frequently fallible, favoring those who have more access to judicial instruments and not those who make “social” use of the land as mentioned in the Constitution. “It is understood that whoever has the documents owns the land, but in Brazil that is a travesty.”

Liliane has noticed throughout her years monitoring land disputes that, in general, judges in district courts rule in favor of farms and companies who present documents without checking if those do indeed prove rightful ownership. According to her, judges will seldom provide their arguments along with a ruling; often simply citing the decision was based on “submitted documents”. The problem is that on so many occasions, the submitted documents are not official. “Time and time again, I see rulings issued with basis on an online document acquired via Incra’s website. A document, whose fine print clearly states it is not valid as official proof of ownership.”

Liliane believes that rulings, such as the one in favor of the Cacimbinha and the other communities affected by the Condomínio Estrondo are “completely unusual”. She has worked on other cases where, even when proof that families had inhabited the land for over 100 years was provided, the supposed “new owners” received favorable rulings. “It is an institutional problem where most of the time, preliminary decisions will accept buying and selling contracts for the land as proof, but that is not enough to rightfully establish possession of the land.”

According to data from the Associação de Advogados dos Trabalhadores Rurais da Bahia (Association of Lawyers for Rural Workers of Bahia), it is common for grileiros A person who illegally takes possession of land. to buy small plots from local residents, pool those with other plots, and file for ownership of the whole property at the registry or with a notary. In other cases, land deeds attesting ownership are forged. According to the Greenpeace report on the Matopiba area, “many times, local registries are complicit in this practice, knowingly ratifying documents of questionable origins that are later used in court to establish ownership of a property.”

In the state of Bahia, the highlands and plateaus were appropriated for mechanized agriculture in such a way. These areas, frequently used by traditional populations to graze livestock or gather fruit and plants, were essential to the maintenance of their traditional ways of life. Gradually, as the landscape of the plains has been substituted by farmlands, communities have been restricted to the valleys or have migrated to urban areas.

As Lusineide tells us, life in the valleys has been transformed. Communities used to live off the fruit of the land and the cultivation of local crops. They were completely integrated with the Biome, but are now worried about their survival. Water is scarcer, erosion of the plains has increased, and the Cacimbinha community fears it will be a victim of diseases caused by the pesticides used on the farmlands. ” We are down here and they are up there, dumping all that poison into our springs,” she laments.

” If we live off what nature provides, how can we go on like this? How will we live a few years from now?”

Lusineide dos Santos