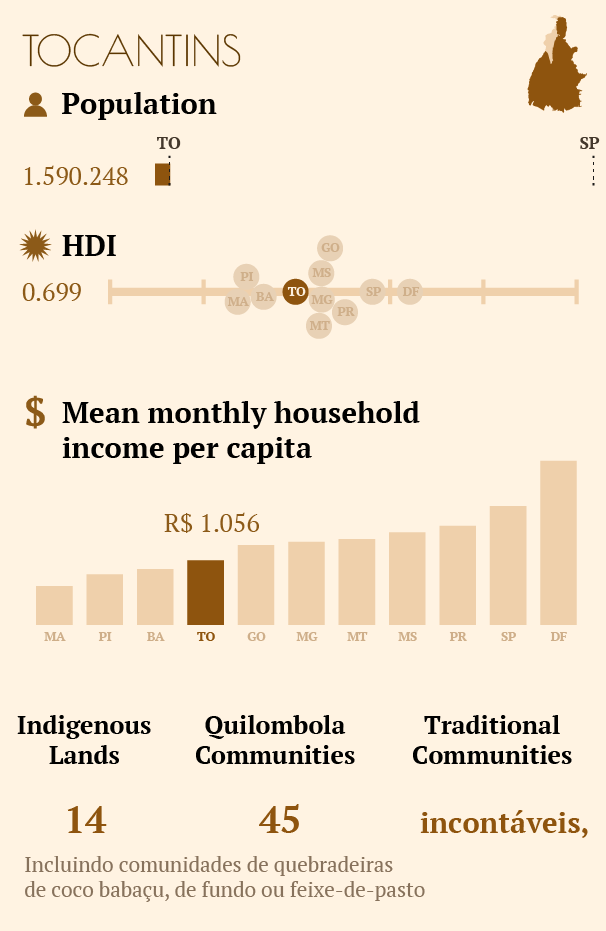

Tocantins

Experience and coexistence

ANA MUMBUCA

They gather around the fire when night falls. Residents of the quilombola community of Mumbuca are used to eating roast potatoes and manioc, and having serious conversations by the fire while someone plays a viola de buriti (stringed instrument made from the buriti palm tree). In the middle of the Jalapão, the collective way of life is an integral part of this traditional community that has been living in the Tocantins Cerrado for over two hundred years.

” Living together is our ancestral heritage. We live together with the frogs, the monkeys, the Cerrado, our families,” says Ana Mumbuca. She is thirty-one years old, but her ID says thirty-three. Apparently, there was a mix-up when her father registered her at the age of thirteen.

This mix-up is significant though: ” The mumbucas did not need any papers before”, writes Ana in her master’s thesis. In her text, she explains the difference between her community’s way of life and the institutional, written records of the country. “Registries don’t have any documents about us, and our histories are nowhere to be found in books,” she states. For many generations, the Mumbuca life has been recorded orally.

” We have a different understanding of time, one based on events and happenings, and not on the western calendars.” For Ana, the source of her way of thinking comes from African and Indigenous thought processes, based more on facts and passage. The years are identified as ” the period of the great hail storm” or ” the time when the Bilau Lake dried.” Their manner of relating to time is reflected in the peculiar way of life in Mumbuca.

” We live our daily lives in accordance to the art of serenity. Everybody takes care of each other.”

Ana Mumbuca

This serenity comes, in part, from the community’s relationship to the surrounding environment. The Mumbuca community is located in the Jalapão, an oasis of crystalline waters in a semi-arid region.

Dunes, plateaus, and plains where lakes form and rivers of potable water flow, characterize this Cerrado landscape located in the east of the state of Tocantins. This area of breathtaking beauty and abundance of natural resources, barely affected by human devastation, sustains the very specific ways of life of the seventeen quilombola communities that inhabit the Jalapão.

Throughout many generations, the traditional communities of that area have developed specific agricultural systems and techniques to farm in a sustainable manner, integrated with the Biome. Their techniques coupled with the gathering of fruits and keeping of animals for food, maintain the balance between the families and nature.

Rowing in the sand

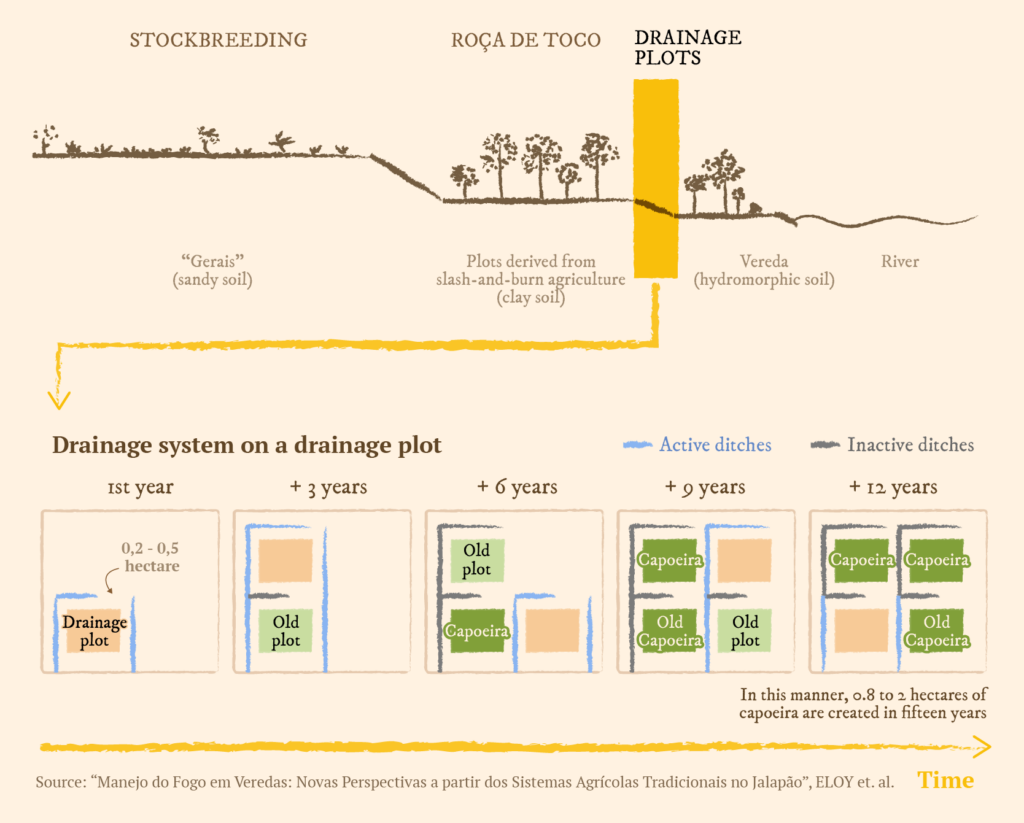

Ana’s forefathers learned how to manage the sandy soil in order to cultivate crops. The techniques developed in the region, called Roças de Esgoto or Rego (Drainage or ditch plots) has been studied in recent years by researchers like Ludivine Eloy via Brasília University and the National Center for Scientific Research in France.

In some of her articles, she demonstrates the high productivity of the drainage plots and explains how the drainage system developed by the local populations allows families to produce food all year long. ” With these techniques, half an hectare of crops will feed a family of ten for ten years, ” Ludivine points out. In addition to the sophisticated drainage techniques of the Jalapão, she also highlights the variety of techniques in the cultivation of rice of the Kalungas in Goiás.

Ludivine explains that the local population has a deep and refined knowledge of the environmental dynamic of the area where they live, which has allowed for the refining of agricultural systems throughout the years. ” There is a tremendous agricultural heritage of the quilombolas of the Cerrado that remains unknown, and invisible,” she says.

In the Mumbuca community, traditional plots and farms make up the basis of their diet, which is complemented by products bought in the supermarket or gathered in nature. ” When we kill a paca (*large rodent) for food, we know when and how to do it. It is not done in a way that is harmful to the environment,” comments Ana Mumbuca.

In one of her studies, Ludivine also points out how the traditional use of fire is a part of the agricultural and ecological conservation processes in savannah Biomes, and does not cause environmental damage. This is cause for some friction in the relations between rural populations and the management of conservation areas.

In 2001, a part of the region was declared the Parque Estadual do Jalapão (Jalapão State Park), a fully protected conservation area. In practical terms, this means the demarcated area became an area of environmental protection controlled by the government. The establishment of the conservation area ensured the protection of the water oasis but also brought about obstacles to the life of the communities living there. ” They took our existence for granted when they created the park with no public discussion on the matter, without even talking to us, ” says Ana. Back then, communities received fines for plowing the land for plots, and for using fire to clear veredas (a palm tree swamp-like vegetation area of the Cerrado).

The conundrum extended into 2012, when the ICMBio signed an agreement with the association representing the residents who live in and around the preserved areas, regularizing the use of fire and other agricultural practices. According to Ludivine, the root of the conflict between the government’s environmental protection rules and the communities was a lack of scientific understanding of the ecological impacts of these non-mechanized, and small-scale agricultural activities in the veredas of the Cerrado.

With this agreement, the communities were heard and according to Ana, this gave way to a new mindset. ” At the time when the park authorities approached us saying we would have to leave, we didn’t even know what a park was”, she remembers. It was hard to fathom back then how the rules of the conservation decree, were actually already a part of the communities’ daily lives. ” Today we have learned to cohabit, the park and us. We have realized it is possible to co-exist.” she analyzes.

Today, the Jalapão has a mosaic of different kinds of conservation areas. In addition to the state park, there is the Parque Nacional das Nascentes do Rio Parnaíba (National Park of the Parnaíba River Source), the Áreas de Proteção Ambiental (APAs – Environmental Protection Areas), Serra da Tabatinga e Jalapão (Tabatinga and Jalapão mountain ranges), and the Estação Ecológica Serra Geral do Tocantins (Tocantins Serra Geral Ecologic station), one of the largest of its kind in the country.

Fear of being thirsty

Preservation is an important concept and is becoming ever more present in the Jalapão area. This is because over the past decade, local populations have been witnessing significant changes in the region’s climate and environment.

” Perennial rivers have disappeared, ” says Ana. In her region, water is at the center of their worries. Around the protected area, the lowlands are drying up and springs are moving.

” The ecosystem is drying up, and in my opinion this cannot be attributed only to a decrease in rain.”

Ludivine Eloy

The landscape of the eastern part of Tocantins, like the west of Bahia, has been transformed by the expansion of monoculture, particularly soy cultivation. The advance of the agricultural frontier over the Matopiba attracts agribusinesses and worries local communities and researchers.

Today, the expansion of soy in the region depends on irrigation systems. Ludivine points out that mechanized irrigation, such as the one used on large farmlands, has a strong impact on all the hydrologic cycles of the region. ” These are communities suffering from extraterritorial environmental consequences, so it is hard, ” she says.

Mateiros, the municipality where Ana’s community is located, borders the state of Bahia and the region around the municipality of Luís Eduardo Magalhães, nick-named the “capital of agribusiness”. Concerns about water have been central in this entire region of the Matopiba.

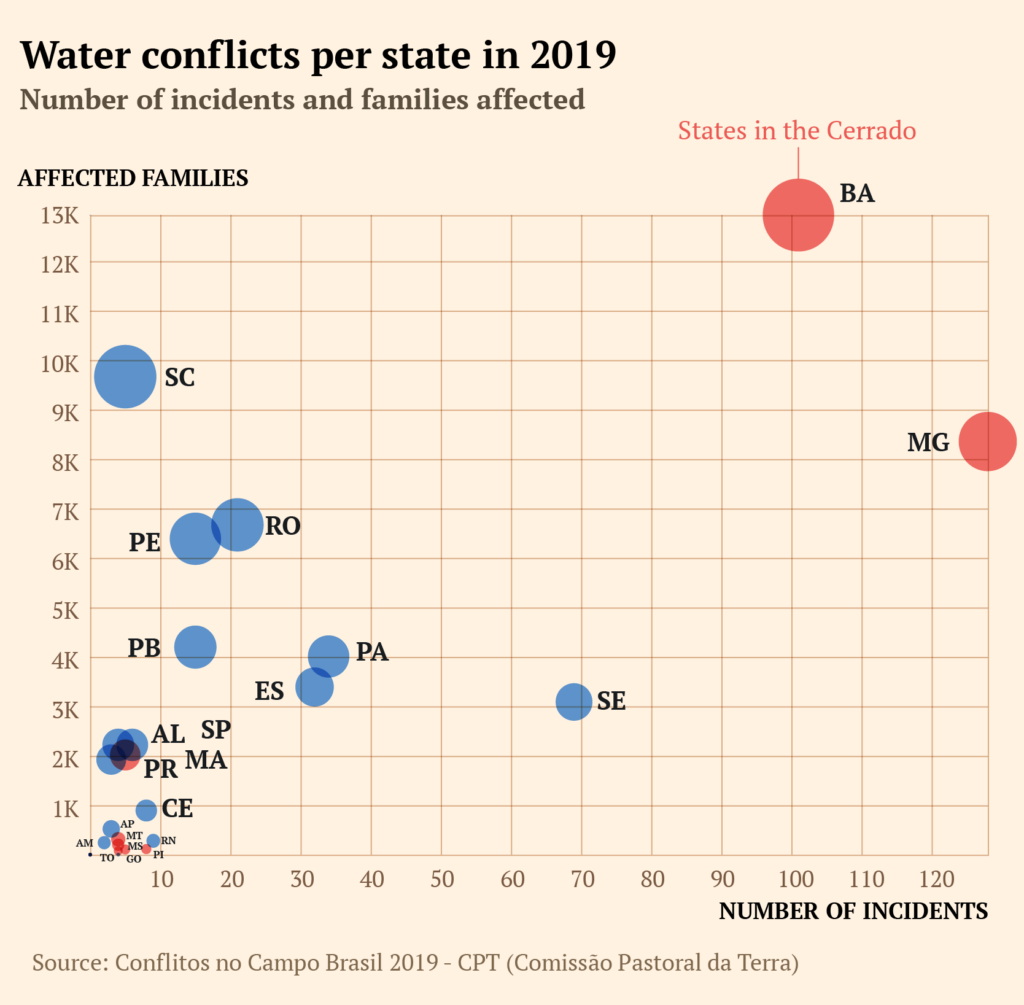

In Correntina, a nearby city in the west of Bahia, the water conflicts reached a dramatic point when the water of the main river flowing through the region began to be used by businesses. The Inema (Instituto do Meio Ambiente e Recursos Hídricos – Institute for the environment and hydrologic resources) granted Igarashi farm the right to extract the equivalent of 106 million liters of water from the Arrojado River per day. According to Cleidiane Barreto, a leader of one of the communities suffering from the drought that occurred as a consequence, that quantity of water would be enough to supply a city of thirty thousand inhabitants for a month.

The traditional communities of the west of Bahia, called fundo de pasto or feixe de pasto, have a similar agricultural system to that of the Jalapão quilombos. ” It is a century-old irrigation mechanism where rivers are drained through ditches, the so-called regos (ditches), which pass between the houses and take the water to all the plots,” explains Ludivine.

In this part of the Cerrado, which is already significantly surrounded by soy farmlands, dozens of families have been left without the water of the regos in recent years. In the case of the Correntina municipality, the state prosecution office of Bahia defends the suspension of new authorizations – official authorizations granting the use of water- and a revision of those already granted, along with an update of the technical criteria for new concessions.

According to Ludivine, the increase of water concessions given to farmlands is at the root of the conflicts in areas of the Cerrado both in Bahia and Tocantins. With the extraction of water, a lowering of the groundwater reservoir occurs as well as the migration of springs.

” Most often than not, the communities do not have the means to prove the correlation between the lack of water on their territories and the use of water for irrigation of soy farmlands, ” she points out.

Agribusiness’ future impact on this region of the Cerrado is still unknown, but the inhabitants of the Jalapão are frightened. They often say, “There is no way to be sure if the rivers they know will still exist ten years from now.”