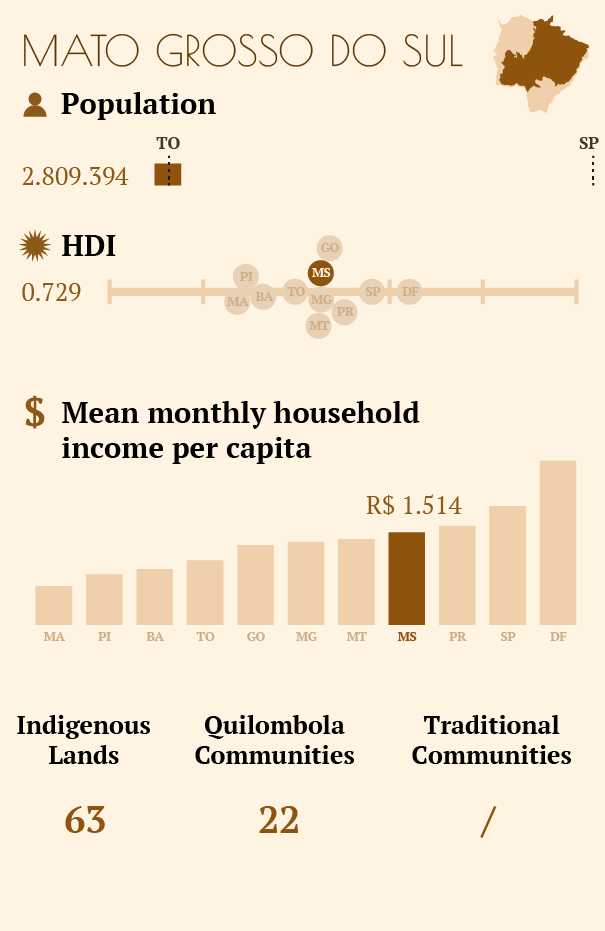

Mato Grosso do Sul

The expansion of monoculture

PRETA

There are fruit-bearing trees growing in the middle of the pasture. The native vegetation resists amid the livestock on the Andalucia rural settlement. This rare image on the pastures of Mato Grosso do Sul is common in Rosane Sampaio’s community. “Here, we know that clearing all the plants for pastures is not the way to go. We have learned about the benefits of the vegetation,” she explains. Known as Preta, she is a reference on sustainable practices for rural communities in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul.

As an outcome of the land reform enacted twenty-four years ago, Preta and 163 families earned the official recognition of their rural settlement by Incra. Today, Andalucia is known as a hub of sustainable development in the Cerrado. There, Preta heads the Centro de Produção, Pesquisa e Capacitação do Cerrado (Cerrado center for production, research, and training), a sort of laboratory that helps farming families generate income.

Born from the efforts of a group of women, the Center now has cooperative fruit and nut-processing installations, organizes training workshops on gathering for other communities, and is a space that fosters and strengthens political power for women.” We try to develop methods to get ‘new money’, means to add to families’ incomes with what the land has to offer,” Preta explains. ” But it has not always been this way; we did not have the knowledge of sustainable practices before,” she says. As an example, she explains how families of farmers used to clear a whole area for pasture. ” The mindset used to be to get rid of all the scrub vegetation because it was ‘ugly’.”

Preta explains how her own thinking began to change early on in the creation of the settlement. ” We were fortunate that a project of the university [Federal university of Mato Grosso do Sul] began to work with us at that time, and brought up environmental issues and ideas on how to ‘act differently’.” The university’s outreach project offered technical advice and workshops to the recently settled families. Preta says it was an eye-opening experience for the entire community.

” We started developing different gathering techniques as we realized what being sustainable meant,” she says. Throughout the years and harvests, the families of Andalucia honed their practices on gathering native fruit of the Cerrado and collected their expertise in a Manual de Boas Práticas (Guide to Good Practices) written collectively. The text explains, for example, how to assess the amount of fruit that should be left on a tree so animals can feed, and later, so the soil will in turn be nourished. It also describes when to begin a harvest or gathering, and the importance of not gathering more than 70 percent of the fruit on a tree or plant.

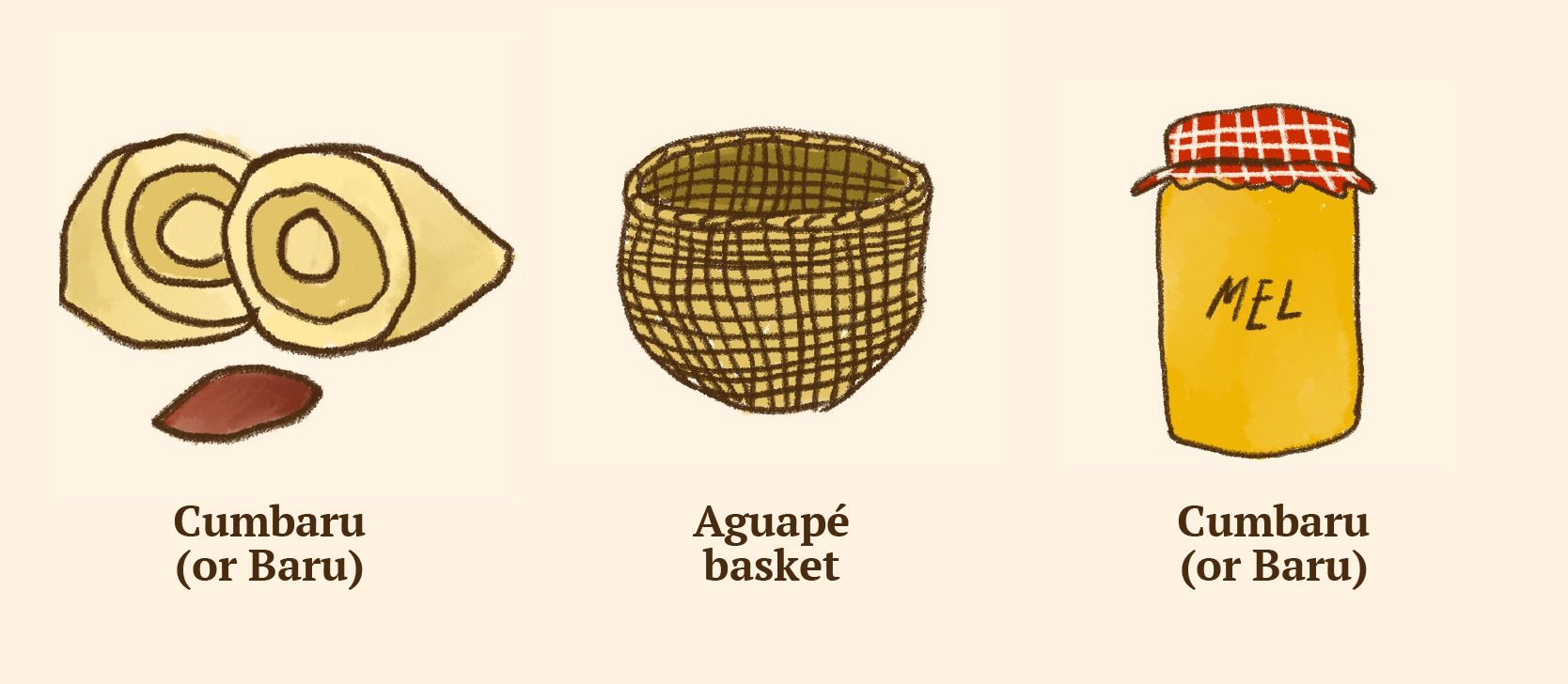

” Today the community has the required expertise,” says Preta. In 2020, the native fruit-processing manufacture that is part of the Centro de Produção, Pesquisa e Capacitação do Cerrado had a baru stockpile of close to thirty-five tons. This corresponds to 1.700 kilos of the baru kernel, the chief good of the Andalucia community.

” Family farms are a treasure, a jewel hidden in a chest that governments have yet to discover before they can realize the potential that exists in the settlements.”

Preta, Rosane Sampaio

The baru is native to the Cerrado and is traditionally part of the food source of rural populations of the Planalto Central area. Inside each thick-skinned fruit is a kernel rich in minerals and vitamin E. Once peeled and roasted, it can be consumed raw or added to recipes. It tastes milder than peanuts and it is similar in texture to the creamy, oily texture of the castanha-do-pará (Brazil nut).

However, the gathering of baru is not the only income-generating activity on the settlement. The families also work with cattle for milk, meat, and agriculture.

Today, the ‘agro-gathering’ (from agroextrativista – a combination of agriculture and gathering) women of the settlement are part of the Cerrapan, a network of farming women of the Cerrado and Pantanal Biomes formed four years ago. Together, farmers from eight rural communities of both Biomes develop strategies for sustainable gathering and commercialization of native fruits.

Bocaiúva, laranjinha-de-pacu, jaracatiá, and baru are some of the fruits gathered and processed that have begun to reach new markets. In recent years, the agro-gathering communities have created new recipes and alternative means of commercialization of their products. With the support of nutrition experts and food engineers of the state’s federal university, they have honed processing techniques and now produce jams, purees, and other value-added products.

Bocaiúva (or Macaúba)

(Acrocomia aculeata)

Its flesh is rich in beta-carotene, and it is a natural source of vitamin A, copper, potassium, and zinc. It is an antioxidant, and is rich in Omega 3,6, and 9. It can be consumed raw or processed: the flesh can be used for sweets and sauces and the flour for breads and pastas. The kernel is used for sweets and provides a rich oil.

Laranjinha-de-Pacu (or Moranguinha)

(Pouteria glomerata (Miq.) Radlk.)

Is rich in vitamin C, iron, and copper. Its popular use is as an anti-ageing food. It has a nice, mild and sweet perfume and a bitter taste.

It can be consumed raw and its puree can be used in juices, ice creams, and jams.

Acuri (or Bacuri)

(Attalea phalerata Mart. ex. Spreng.)

It is rich in pro-vitamin A, copper, magnesium, and potassium, which aids in regulating blood pressure and in the prevention of heart complications.

It has a mildly sweet taste and its flour can be a substitute for manioc flour in various dishes like porridge, pirão, and as batter to fry meat and fish.

Jaracatiá

( Jaracatia corumbensis Kze.)

It is rich in vitamins A, C, and E, copper, magnesium, and potassium. It is a source of fiber and aids in digestion, strengthens the immune system, and is anti-ageing.

Its texture is similar to that of the green papaya and it is used in the preparation of canned fruits, sugar candy, and jams.

In addition to stimulating economic autonomy for women, Cerrapan also provides support to strengthen communities fighting for a better quality of life. The network of farmers seeks to increase its presence in discussions on public policy and to amplify the voices of rural communities. In the Corumbá municipality, for example, the network’s representatives are part of the Comissão Intersetorial de Saúde das Mulheres (inter-sectorial commission on women’s health), which is integrated to the local management of the SUS (Brazilian public health care system).

An outlier in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul

In the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, the Cerrapan organization has brought about new possibilities of production and farming, and new means to generate income while protecting the environment. ” The Andalucia settlement is an example of how technical support can make a difference,” says Nathalia Ziolkowski, a sociologist working through the NGO Ecoa with rural groups of women in Mato Grosso do Sul. According to her, rural communities generally deal with an everyday lack of assistance. Isolated from public services due to poor roads, they have a hard time accessing government aids.

“Of course, every territory has its own characteristics, but in a general way, here in Mato Grosso do Sul, everyone suffers from one thing: the absence of the State,” she points out. In her opinion, there is a lack of technical support offered to communities who wish to develop new means of production and farming. Surrounded by pastures of cattle raised for meat and grain farmlands that follow the hyper-mechanized model of export agriculture, communities are left with few options to generate income on small plots.

Serial forest planting

Mato Grosso do Sul is a farming state. According to data from the IBGE, 85,54 percent of the state’s area is occupied by agriculture or stockbreeding. In 2019, the state was the second largest producer of cow meat in the country, the fourth largest producer of corn, and fifth largest producer of soy. According to a report by the state’s agriculture and stockbreeding federation (Federação de Agricultura e Pecuária), the growth in productivity of the agriculture and livestock sectors has accelerated.

The document states that the increase in the production of grains and meat comes from greater professionalization of the sector and the advent of new ways of occupying the land through applied technology. The record numbers in productivity achieved confirms the existing incentive given to large-scale production geared for export.

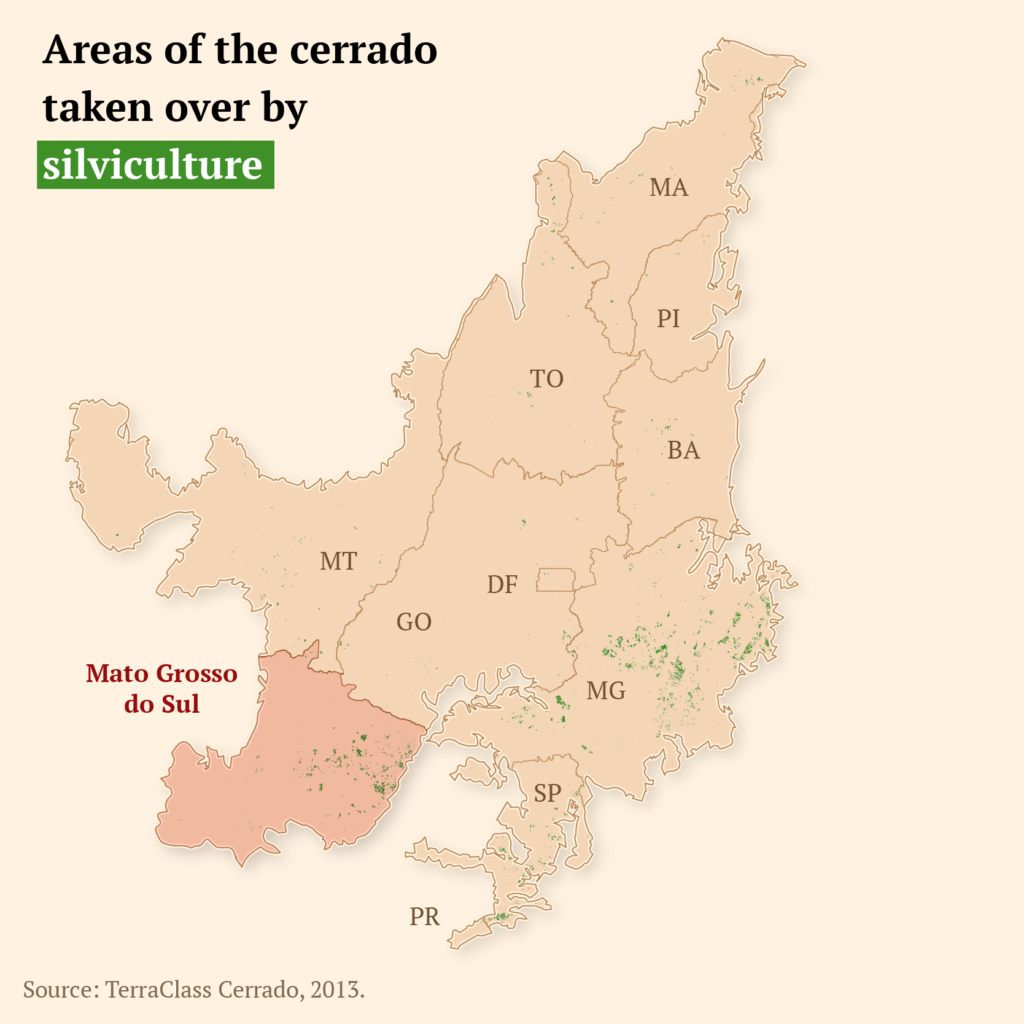

Among those seeking an entry into foreign markets, Mato Grosso do Sul distinguishes itself in the cultivation of so-called “forest products”, whose export grew by 84,8 percent between 2015 and 2019. The most recent official data collected by the IBGE in 2017 reveals that areas of “planted forests” increased by 862 percent over the last ten years, with eucalyptus being the main cultivation. There has been a significant investment, primarily since 2006, in the production of wood for pulp in the eastern region of the state, precisely the area where remnants of the Cerrado still exist.

In general, the expansion of the silviculture of eucalyptus in Brazil occurs mainly over this Biome. According to data from the Ministry of Agriculture’s last study, close to 1.5 percent of the Cerrado has been transformed into planted forests, most of which are eucalyptus.

Researchers are worried about the introduction of eucalyptus monoculture in the remnant areas of the Cerrado. The main issues and impacts concomitant with this particular cultivation are the drying and desertification of the soil, aggradation as a result of the silting of rivers, compromised groundwater reserves, and loss of biodiversity.

In addition to the environmental impacts enumerated by several studies, there are also worrying social impacts linked to the monoculture of eucalyptus. An article analyzing the expansion of silviculture over the Maranhão Cerrado reports profound dissatisfaction of the local rural population with the arrival of single-species forests. The impact of the monoculture as related by the local population includes aggradation of the rivers, a weakening of water sources, and an increased difficulty in the cultivation of local crops; impacts which affect the local population’s food source and well-being.

Future paths

Monoculture, and not only eucalyptus, is expanding in Mato Grosso do Sul and relies on government subsidies. On the other hand, production of food goods by small farmers is in a dire situation, as farmer and agro-gatherer Preta points out.

” Family farming has been facing a pandemic of neglect for some time now.”

Preta, Rosane Sampaio

Nathalia, a sociologist who works with rural communities in the state, says plans to incentivize organic family farming do exist. However, these initiatives many times never leave the page. ” We see policies being scrapped and their teams left with no support,” she points out. She believes there is a lack of focus on sustainability, one that goes beyond the cultivation of organic cow meat in the Pantanal, a project already in expansion.

Yet, in some places like the Andalucia settlement, the lack of technical assistance can give way to innovation and hope. According to Preta, there are also positive signs: ” society is opening up to healthy products, to real fruits,” and the agro-gathering families will continue to supply and strengthen the demand for fruits of the Cerrado that generate income and help the Biome stay on its feet.