Minas Gerais

The first agricultural frontier

CÉLIA XACRIABÁ

Célia awakens as the sun rises. She gets up and looks out her window; she enjoys seeing the daybreak. A sparkling pink ipê (Ipe tree) is blooming right outside her room. Célia takes a picture of the colorful tree and posts it on social media with the message, “Morning in the strong Cerrado”. Cerrado is a Brazilian ecoregion, a tropical savannah.

Seeing the ipê close by makes her feel good. The tree means she is home on her territory, where she belongs, as she likes to say. Célia is from the Xacriabá, a people who have inhabited the northern region of the state of Minas Gerais for over 500 years. She compares her people to the landscape and flora of her region, because just like the trees of the Cerrado, their roots go very deep. For Célia, there is a parallel between the resistance of the people descending from the Macro-jê linguistic line -originally from central Brazil- and the strong roots of the vegetation of the Biome that they integrate so harmoniously.

Today the Xacriabá live on the fringe of the Minas Gerais Cerrado, in a flat region with gnarled trees, close to where the land dries up and turns into caatinga (Brazilian xeric bioregion, shrub land). They used to live closer to the banks of the São Francisco River but have been pushed out to the dryer areas along the years.

The river plays a central role and is of paramount importance in the history of the Xacriabá. Célia says the word that gives her people their name means “good rowers”. Her ancestors lived on the banks of the great river that nurtures the northeastern region of Brazil and were known to be consummate rowers. Today, far from the waters, Célia will hear comments like, “oh, you are Xacriabá? Then you can fish and are a good and swimmer.” But her reply is an unfortunate “no”, seeing as today, women and young people in particular, do not enjoy the river lifestyle of older days. “I tend to say the only reason we did not drown in the river is because the loss of that river life has already drowned us,” she laments.

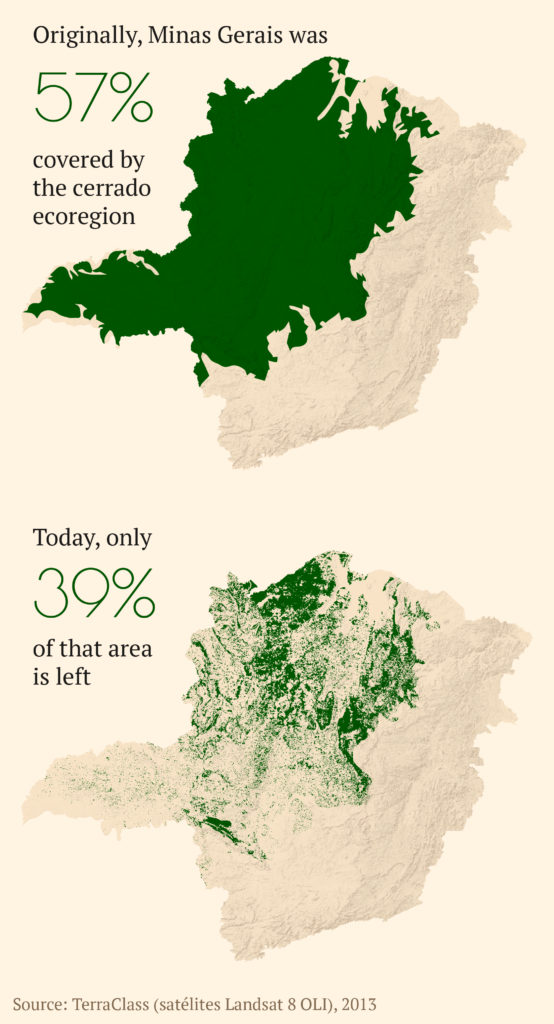

The histories of these indigenous peoples and other traditional communities of the Cerrado are scarred by memories of dispossession and appropriation of their territories. Memories of a push, intensified since the 1970s by the advance of the government and agribusinesses and the transformation of the Cerrado into farmland and pastures. According to researcher and sociologist, Mauro Pires, the occupation of the Cerrado as an agricultural frontier began precisely in Minas Gerais. He states that, “The technological developments of the green revolution in the Cerrado Biome were first tested there [in Minas Gerais].” With the development of soil correction and large-scale planting techniques – techniques of the aforementioned green revolution – the regions of the Minas Gerais Cerrado were quickly overtaken by a “more capitalist” occupation of the territory, according to the researcher.

The future past

Observing how regions of the Minas Gerais Cerrado have been converted into enormous pasture and farmland areas, helps to better understand the dynamics of the agribusiness occupation of the Cerrado in general. After the introduction of large-scale cultivation technologies and the construction of large infrastructure works, lands that farmers and agribusinesses previously did not value, suddenly became prized.

Pires explains that there are similarities between what happened in Minas Gerais in the twentieth century and what is now happening to parts of the Cerrado further north, at the junction of the states of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí, and Bahia – the area known as Matopiba.

As deforestation advances, making way for new lands to be used in agricultural production, the people previously living in those areas search for means to endure. What happened in Minas Gerais is essentially what happens all over the Cerrado. The more agribusiness advances to the fringes, to areas far removed from the country’s hubs, the more it affects traditional communities. Throughout the history of the colonization and occupation of Brazilian lands, hundreds of local peoples have been wiped out or forced off their native lands.

“Older communities and elders tell us of how their groups dispersed and their ways of life were abandoned in an attempt to adapt to urban living,” says Pires.

The Xacriabá people, for example, were declared extinct around the 1960s. The official history did not account for Célia’s relatives’ existence and presumed they had all been “assimilated”. The Xacriabá only made their way back to the federal government’s list of indigenous peoples when, at risk of losing their lands, they organized and asked for protection. Today, the Xacriabá are the most populous indigenous ethnicity of Minas Gerais and make up for 75 percent of the population of the district where Célia’s territory is located.

The Xacriabá forefathers had to fight long and hard for official recognition and protection of the lands they inhabit today. With the intensification of advances by farmers seeking land in the region in the1970s, chiefs from that community traveled countless times to Brasília to demand the demarcation of their original territory. In the 1980s, the tension of the dispute for land in the region gained national attention with the news of chief Rosalino Xacriabá’s murder by gunmen. He became a martyr for the cause and the movement gained strength and traction after his assassination. Finally, in 1987, the Xacriabá indigenous land was officially demarcated. According to indigenous leadership though, only a portion of their original territory is officially protected. Today, they seek to increase the reservation so they can once again have access to the São Francisco River.

” The fight for our territory is our main fight, because without land, we have no home. If you have a place to come home to, then you have a lap to sit on, you have a mother, and a cure.”

Célia Xacriabá

The territory Célia speaks of is something much greater than a plot of land or the boundaries of a property on a map. For the communities of the Cerrado, the land is the provider of life. The life of the Xacriabá, like that of the geraizeiros, the quilombolas, and other traditional communities, is directly linked to, and integrated with the Cerrado. Their daily activities require so much of the Biome, and their lives greatly depend on how they manage and work with what nature provides.

Long-term Strategies

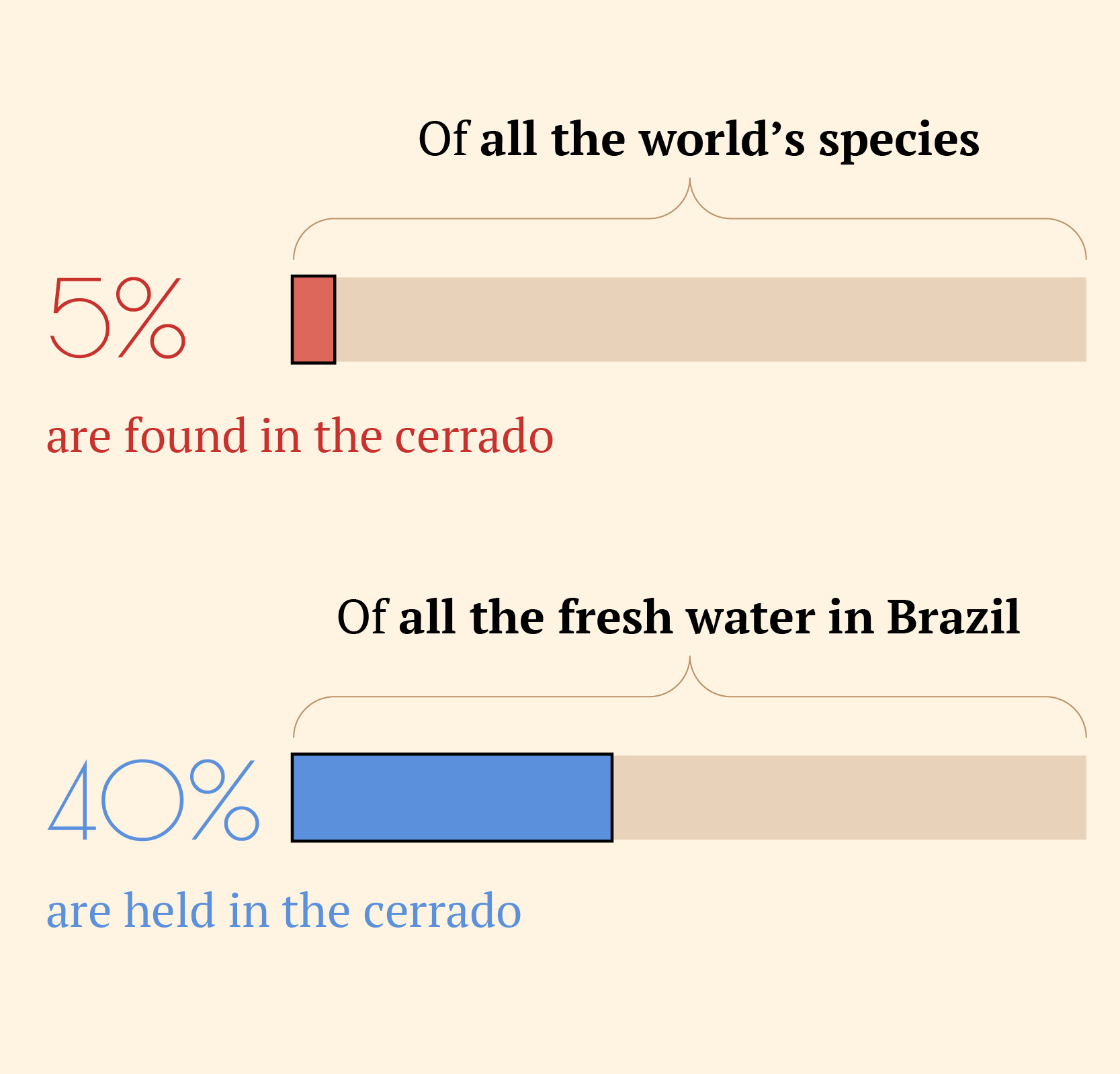

And the land has much to give in the Cerrado. The enormous biodiversity of this Biome contrasts with its reputation of having poor soil and being characterized by vast empty stretches of land; dry and withered, with few inhabitants, or wildlife.

The abundant groundwater found in areas where the Cerrado is still preserved is essential to the existence of local communities and their everyday work. The fruits of native trees are a source of food and income and the roots and barks of trees and shrubs are the natural medicine that has kept countless generations healthy.

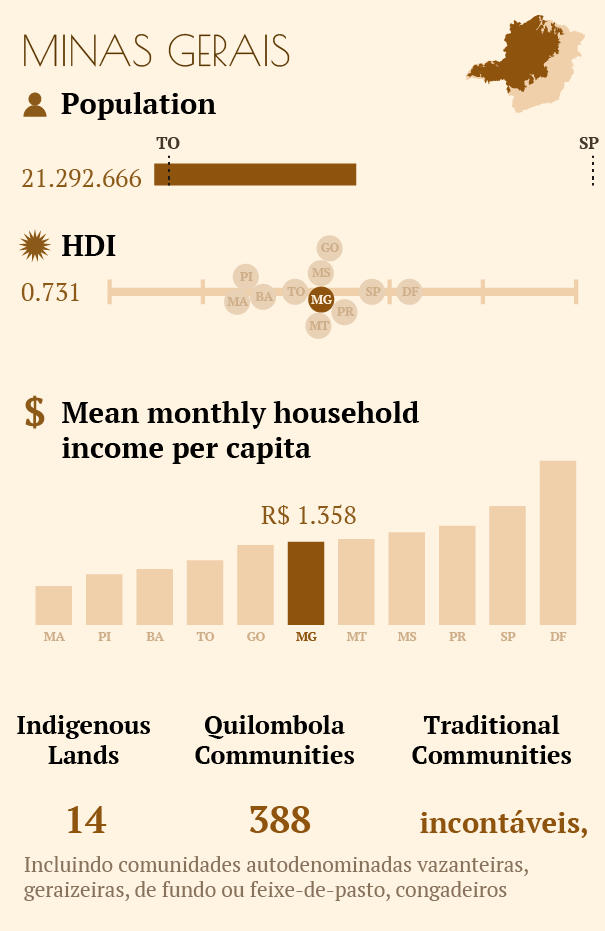

The Minas Gerais Cerrado has been home to dozens of traditional peoples and communities for a long time. Aderval Costa, an anthropologist and researcher at the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, (Minas Gerais State University) and director of a project that charts the locations of traditional communities in the state, explains that, “according to studies, it is estimated that one third of the territory of Minas Gerais is comprised of terras devolutas. Government land with no previous or current private ownership -even if occupied- and no ascribed use. ” In practice, this means the people occupying these areas never obtained, or could never procure the documentation to prove ownership of the lands they live on. “These lands are in the state’s possession but do not necessarily belong to the state.” he affirms.

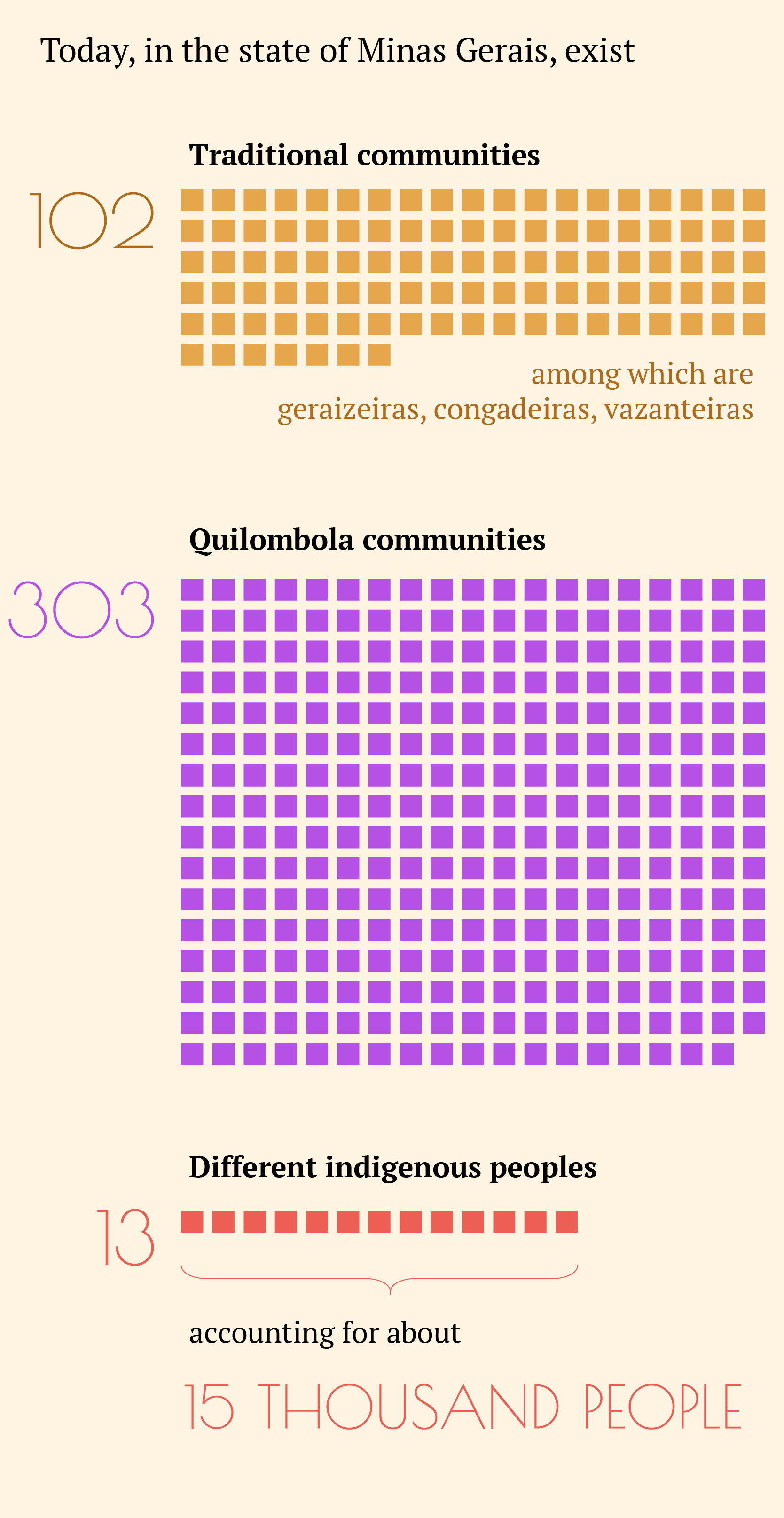

It is hard to pinpoint with certainty just how many traditional communities and indigenous peoples inhabit the state of Minas Gerais. What is certain, however, is that there is an enormous diversity of groups inhabiting the land, each with very unique and specific ways of life. In 2014, a state law was passed to promote the development of these communities. The law emphasizes the recognition and protection of the communities’ lands, of their social and environmental rights, their cultural identities, and their social/organizational structures. Aderval believes this is a landmark achievement because it guarantees these rights by law, as opposed to the federal law in place that only recognizes the rights of traditional communities.

Other communities such as the vazanteiras, the povos de terreiro, the congadeiros, caatingueiros, veredeiros, faiscadores garimpeiros, and others, exist in addition to the indigenous peoples, quilombolas, and geraizeiro communities. Despite being different from one another, all are considered traditional communities because they live in a balanced and sustainable way within the Biome and depend on the natural resources found on their territories. Having lived in a specific location for many generations is also a measure, and these groups also all self-identify as unique cultures. Other important characteristics of these communities include the importance given to rituals associated with fishing, hunting, or harvesting, the deep knowledge of the natural cycles, and how to manage the local habitat and wildlife.

Over the centuries, traditional communities in Minas Gerais have developed strategies to survive and cohabit with the Biome, creating a symbiotic relationship with the ecosystem. They fish, hunt, cultivate the land, and make it productive in a variety of ways throughout the various landscapes of the Minas Gerais Cerrado. Some examples include hillside farming, cultivation deep into the valleys, shepherding and grazing of livestock on the fields, and harvesting of fruit and plants on the plateaus.

Mônica Nogueira, an anthropologist who has been studying traditional peoples of the Cerrado for over twenty years, explains that local communities have developed very refined knowledge of the flora and fauna, and biological structure of the Biome. For that reason, she believes it is not only the land that suffers from deforestation, but the devastation of the Cerrado also entails a loss of human knowledge.

She warns that the knowledge acquired and developed by local communities is under constant threat, as are the 952 species of plants and animals of the Cerrado currently at risk of extinction according to studies done by the Plataforma Brasileira de Biodiversidade e Serviços Ecossistêmicos (Brazilian platform for biodiversity and ecosystem services). The change in the landscape of the chapadas (plateaus) after the arrival of the eucalyptus plantations is a clear example of that in the state of Minas Gerais. Various species important to the geraizeiro communities are no longer available. According to the researcher, in a few generations, the knowledge of those species, such as the nutritional and medicinal properties of certain plants, will likely be forgotten.

In Célia’s view, ancestral wisdom is also an essential heritage. She is the first Xacriabá to have earned a master’s degree, but believes that thanks to the knowledge of her people, science had already been a part of her life long before she went to university. Célia has come to realize that the elders of her tribe are true doctors who posses a deep and encyclopedic knowledge.

” So to me, before the first indigenous doctors of the universities existed, there were the Xacriabá midwives. They certainly occupy another place in science, with a knowledge that comes from a science of the land, the science of time and of the invisible.”

“Monoculture is not sustainable; neither on the farmlands, nor as an idea. It creates a sick society.”

Célia Xacriabá

The wisdom of the Xacriabá molds their community’s way of life, and somehow, also guarantees that these people who were once considered extinct carry on living. For Célia, the key to a healthy future for the population as a whole lies in diversity. She muses, ” I keep thinking of minds that only sow thoughts as being like land that only cultivates one plant.” She believes that a society without diversity of people, and without the various ways of life of the communities is like monoculture, and that is not sustainable for long.